Via Dolorosa

Via Dolorosa

The Via Dolorosa (Latin for “Way of Grief” or “Way of Suffering”) is the path that Jesus walked, carrying his cross on the way to Golgotha, the site of his crucifixion, just outside the old city of Jerusalem.

The route traced by Gibson begins in a parking lot in the Armenian Quarter, then passes the Ottoman walls of the Old City next to the Tower of David near the Jaffa Gate before turning towards the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The new research also indicates the crucifixion site is around 20 metres (66 ft) from the traditionally accepted site.

The late-first-century writer Josephus testifies that the Roman governors stayed in Herod’s palace while they were in Jerusalem, carried out their judgements on the pavement immediately outside it, and had those found guilty flogged there. Josephus indicates that Herod’s palace is on the western hill, and it has recently (2001) been rediscovered under a corner of the Jaffa Gate citadel.

Herod’s Palace

The Romans destroyed the old city of Jerusalem in the first Jewish – Roman war in 70 AD. When the Roman Emperor Hadrian vowed to rebuild Jerusalem in 130 AD, he considered reconstructing Jerusalem on the ruins of the old site as a gift for the Jewish people. The Jews awaited with hope, because Hadrian was considered a moderate. But after Hadrian visited Jerusalem, he decided to rebuild the city and name it ‘Aelia Capitolina’ and it was inhabited by a colony of his legionnaires. Hadrian renamed the province Syria Palaestina, and Jews were banned from entering the city, on pain of death, except on the day of Tisha B’Av, the day that commemorates the destruction of both the first and the second temple.

Aelia Capitolina

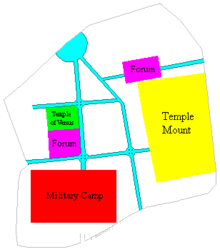

The urban plan of Aelia Capitolina was that of a typical Roman town wherein main thoroughfares criss-crossed the urban grid lengthwise and widthwise.

The urban grid was based on the usual central north-south road (cardo) and central east-west route (decumanus). However, as the main central north-south road ran up the western hill, and the Temple Mount blocked the central eastward route.

A second pair of main roads was added; the secondary north-south road ran down the tyropoean valley, and the secondary east-west road ran just to the north of the temple mount.

The main central north-south road terminated not far beyond its junction with the central east-west road, where it reached the Roman garrison’s military camp. The two north-south roads converged near the Damascus Gate, and a semicircular piazza covered the remaining space; in the piazza a columnar monument was constructed, hence the traditional name for the gate – Bab el-Amud (Gate of the Column).

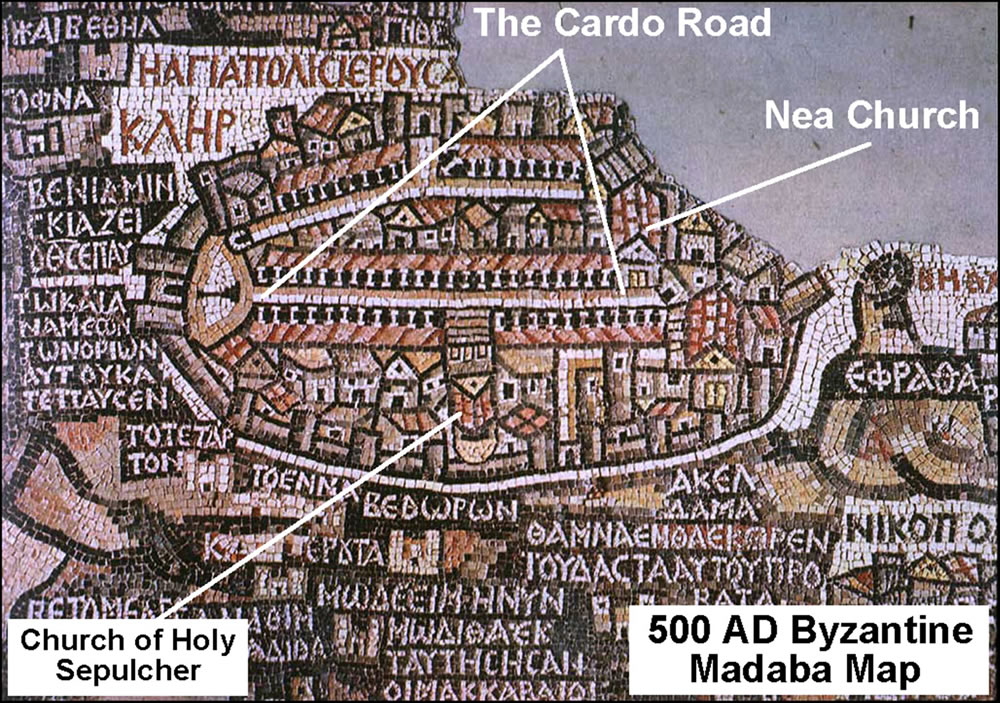

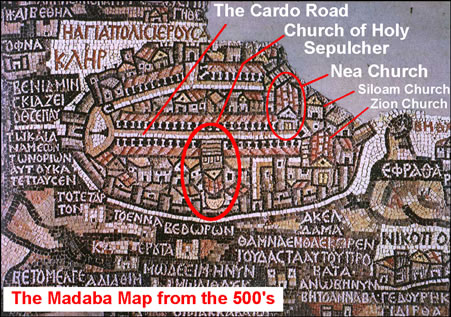

The mosaic (below) shows the Cardo Maximus, the cities main road, beginning at the northern gate, today’s Damascus Gate, and traversing the city in a straight line from north to south.

Madaba Map

The Madaba Map (also known as the Madaba Mosaic Map) is part of a floor mosaic in the early Byzantine church of Saint George at Madaba, Jordan. The Madaba Map is the oldest surviving original cartographic depiction of the Holy Land and especially Jerusalem. It dates to the 6th century AD. The mosaic clearly shows a number of significant structures in the Old City of Jerusalem: the Damascus Gate, the Lions’ Gate, the Golden Gate, the Zion Gate, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the New Church of the Theotokos, the Tower of David and the Cardo Maximus.

The map shows the Cardo as the main road of Jerusalem. Also notice the so called Eastern Cardo which is just above the Cardo Maximus on this map. The pillars along these roads in the photo below are detailed in this map.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is shown with its basilica built in front of Calvary so that it extends all the way to the Cardo. Also, shown on the map are the Nea Church, the Siloam Church and the Zion Church. On Easter each year during the Byzantine era, a very large procession began at the Nea Church and progressed down the Cardo Street to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The Cardo

Ancient Roman arches (below) and their vaulted rooms along the sidewalk of the Cardo in Aelia Capitolina, the Roman Jerusalem.

Part of the ancient Cardo that has been modernized. Notice the pavement and the ancient store fronts which are now home to modern shops.

.

Ecce Homo

The central opening of the Arch of Ecce Homo (Latin – “behold the man”), seen below, is part of an early Roman arch which had triple openings. Built as a triumphal arch in 135 AD, in honour of the visit of Emperor Hadrian, this was part of the Antonia Fortress.

Ecce Homo Basilica

The northern opening of the Ecce Homo Arch is embedded in the Ecce Homo Basilica (dated 1868). This well preserved section is seen in th ephoto below.According to tradition, this is the site that Pilot presented Jesus to the crowds (John 19:5) – “Then came Jesus forth weraing the crown of thorns, and the purple robe. And Pilot saith to them, “Behold the man!”.

This pavement is part of the “secondary” Cardo, which once connected the Damascus (Shchem) gate to the Dung (Ha-Ashpot) gate in the south, as seen in the Madaba map.

A small Fransiscan church (below) is located at the corner of Via Dolorosa road and El-Wad (“The Gai” road). At this corner the road turns sharply to the right, and then starts climbing up the hill with a series of stairs.

Further west up the hill. A small Greek chapel on the right.

Cardo Maximus

This street is one of the busiest in the old city, as it may have been during Jesus’ time. It was an intersection of the Cardo Maximus and a traverse street of the Roman Aelia Captolina and in modern days an intersection of Via Dolerosa and Khan e-Zeit (The Oil Market).

Narrow Alley

The photo below shows the east side of the Holy Sepulchre at Golgotha, which is seen in the far background.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The two grey domes of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher can be seen in the skyline of this photo looking west from the Mount of Olives. The Dome of the rock, which sets in the middle of this photo on the Temple Mount, was built 300 years later to rival the proclamation of Constantine and the Christian world made by the then magnificent Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The church was later totally destroyed by the Muslims in 1009, only to be rebuilt by the Crusaders after 1100.

Holy Sepulchre

“A sepulcher (or if you’re British you’ll spell it sepulchre) is basically a stone room with a stone coffin where your body lies. The word comes from the Latin sepulcrum, which means “burial place,” for obvious reasons. Pronouncing sepulcher could trick you, because the ch actually sounds like a k: “SEP-ul-ker.”

Site of Jesus’ Burial and Resurrection

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher has been destroyed and rebuild several times through the centuries. The church we see today was constructed by the Crusaders. The small grey dome covers the rock of Calvary, and the large dome covers the site of Jesus’ burial and resurrection.

Today’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher sets over two sites:

- Calvary and

- the tomb of Jesus.

Both these sites were in the same garden outside the walls of Jerusalem in 30 AD, and now they are under one roof. John wrote that they were close to each other:

At the place where Jesus was crucified, there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb, in which no one had ever been laid. Because it was the Jewish day of Preparation and since the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there. – (Luke 19:41-42).

Calvary

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is shown with its basilica built in front of Calvary so that it extends all the way to the Cardo. Also, shown on the map are the Nea Church, the Siloam Church and the Zion Church. On Easter each year during the Byzantine era, a very large procession began at the Nea Church and progressed down the Cardo Street to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The area where the Church sits today was a large limestone quarry in 600-700 BC. The city of Jerusalem was to the SE and expanded first to the west before it came north toward the quarry. In an area east of St. Helena’s Chapel in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher the quarry was over 40 feet deep.

The Tomb

In 30 AD, this was the perfect place to cut new graves because of the bedrock left exposed around the quarry, because it had only recently become available so still had lots of available space, and because it was close to the city yet still outside the walls. Jerusalem was, and still is, surrounded by graves that had used for a thousand years leading up to 30 AD. This new garden was indeed a great opportunity for Joseph to be able to cut a grave so close to the city:

Now there was a man named Joseph, a member of the Council, a good and upright man, who had not consented to their decision and action. He came from the Judean town of Arimathea and he was waiting for the kingdom of God. Going to Pilate, he asked for Jesus’ body. Then he took it down, wrapped it in linen cloth and placed it in a tomb cut in the rock, one in which no one had yet been laid. – (Luke 23:50-53).

Four tombs from this period have been excavated.

- One of the tombs was a kokh, a long, narrow recess carved for the placement of a body. Bones were left in the kokh for a period of time, then later collected and placed in an ossuary. Due to this method of dealing with dead bodies, tombs would rarely be “new” tombs, since they were used over and over by a family or a group of people.

- Another tomb found in this area was an arcosoliuim, or a shallow, rock-hewn coffin cut into the side of a wall with an arch-shaped top. This tomb has been chipped away by centuries of pilgrims.

- The third is a large tomb that, like the kokh mentioned above, was found in front of the church in the entry courtyard. Constantine cut this tomb larger to use as a cistern.

- Finally, another kokh tomb was found under the Coptic convent. It is clear and undeniable that the Church of the Holy Sepulcher stands on the site of a burial ground from the time of Jesus in the first-century.

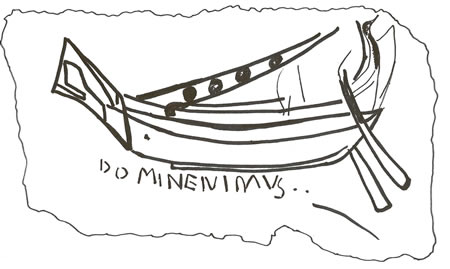

“Lord, We Came.”

The image of a ship painted on a Herodian ashlar found at the bottom of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Chapel of St. Vartan. It is accessed from the left side of the altar in the Chapel of St. Helen, and is next to the Chapel of the True Cross.

Ashlar Stone

Ashlars were placed in rollers like this to be moved to location. This was one of several ways the stones were moved. Stones were also pulled by teams of oxen on rollers.

Hadrian reused the Herodian stones from the Temple to build his pagan shrine over the tomb of Jesus. It appears a Christian pilgrim visited this site after sailing here from a foreign land. He drew the image of his ship with a lowered sail and wrote, “Lord, we came.”

Holy Sepulchre Floor Plan

Acknowledgements: references: