They changed the World

The 19th century was one of the greatest centuries for world missions and reaching the nations for Christ. However, if we want the 21st century to be even greater missionary exploits than any of the former centuries, then we will need to learn from the Christian pioneers whom God used to make the 19th century (1801 – 1900), the greatest century of advancing the gospel so far.

These pioneers and the overwhelming difficulties, dangers and obstacles, which they had to overcome, clearly provide us with the most inspiring examples of Christian endurance, courage, and perseverance – against all odds.

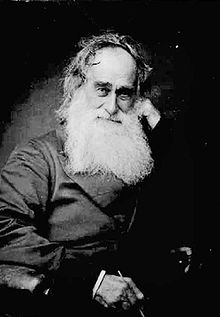

David Livingstone

The incredible adventures of these soul-winners and the achievements and exploits of these extraordinary Christian pioneers have been mostly forgotten in the countries where they originated from. For this reason, that we need to revive some of the achievements and sacrifices of these missionary statesmen and stateswomen. Dr. David Livingstone is one of those people.

Dr. Livingstone, for example, has two towns in Africa named after him: Livingstonia in Malawi and Livingstone in Zambia. Other towns in the content of Africa, which were named after Europeans such as Fort Victoria, Elizabethville, Stanleyville and Salisbury, have had their names changed.

However, Livingstonia and Livingstone remain as a tribute to a man who brought hope and faith to the hearts of Africans, and fear to the hearts of the slave traders. David Livingstone is known as a liberator in Africa.

Whilst the statues of Cecil John Rhodes and many colonial figures, have been toppled and removed, statue of David Livingstone, still retains their prominence and deep respect which the people of Africa still have for this missionary statesman.

Today, our young missionaries going into the mission field have absolutely no cause to complain. When we consider the bad roads, David Livingstone had to trek on, today we drive our four wheel drives.

David Livingstone was born on 19 March 1813 in the mill town of Blantyre, under the bridge crossing into Bothwell, Lanarkshire, Scotland. David, along with many of the Livingstones, was at the age of ten employed in the cotton mill of H. Monteith – David and brother John working 12-hour days as “piecers,” tying broken cotton threads on the spinning machines. He was raised in a Christian home and attended the church of Scotland.

David Livingstone meets missionary Robert Moffat

At age nineteen David and his father left the Church of Scotland for a local Congregational church. Influenced by American revivalistic teachings, Livingstone’s reading of the missionary Karl Gützlaff’s “Appeal to the Churches of Britain and America on behalf of China” enabled him to persuade his father that medical study could advance religious ends.

After reading Gutzlaff’s appeal for medical missionaries for China in 1834, he began saving money and in 1836 entered Anderson’s College (now University of Strathclyde) in Glasgow,and attended Greek and theology lectures at the University of Glasgow.

He applied to join the London Missionary Society (LMS) and was accepted subject to missionary training. He continued his medical studies in London while training there and in Essex to be a minister.

Kuruman

Livingstone hoped to go to China as a missionary, but the First Opium War broke out in September 1839 and the LMS suggested the West Indies instead. In 1840, while continuing his medical studies in London, Livingstone met LMS missionary Robert Moffat, on leave from Kuruman, a missionary outpost in South Africa, north of the Orange River.

Excited by Moffat’s vision of expanding missionary work northwards, Livingstone focused his ambitions on Southern Africa.

Livingstone sailed in December 1840, arriving at Moffat’s mission, now part of South Africa, in July 1841.

Livingstone rapidly attached himself to the plans of missionary Rogers Edwards to found a mission farther north in territory increasingly disturbed by traders, hunters, and African settlers.

Setting up the new mission at Mabotswa among the Kgatla people in 1844, he was mauled by a lion which might have killed him if it had not been distracted by the African teacher Mebalwe, who was also badly injured.

Both recovered but Livingstone’s arm was partially disabled and caused him pain for the rest of his life.

Livingstone married Moffat’s eldest daughter Mary on 2 January 1845. She was also Scottish but had lived in Africa since she was four.

Victoria Falls

Livingstone explored the African interior to the north, in the period 1852–56, and was the first European to see the Mosi-oa-Tunya (“the smoke that thunders”) waterfall (which he renamed Victoria Falls after his monarch, Queen Victoria), of which he wrote (later), “Scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.”

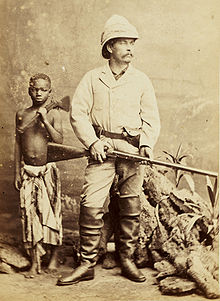

Livingstone the Explorer

Livingstone was one of the first Westerners to make a transcontinental journey across Africa, Luanda on the Atlantic to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean near the mouth of the Zambezi, in 1854–56. The qualities and approaches which gave Livingstone an advantage as an explorer were that he usually travelled lightly, and he had an ability to reassure chiefs that he was not a threat. Other expeditions had dozens of soldiers armed with rifles and scores of hired porters carrying supplies, and were seen as military incursions or were mistaken for slave-raiding parties.

Livingstone on the other hand travelled on most of his journeys with a few servants and porters, bartering for supplies along the way, with a couple of guns for protection. He preached a Christian message but did not force it on unwilling ears; he understood the ways of local chiefs and successfully negotiated passage through their territory, and was often hospitably received and aided, even by Mwata Kazembe.

Livingstone was a proponent of trade and Christian missions to be established in central Africa. His motto, inscribed in the base of the statue to him at Victoria Falls, was “Christianity, Commerce and Civilization.”

At this time he believed the key to achieving these goals was the navigation of the Zambezi River as a Christian commercial highway into the interior. He returned to Britain to try to garner support for his ideas, and to publish a book on his travels which brought him fame as one of the leading explorers of the age.

With the help of the Royal Geographical Society’s president, Livingstone was appointed as Her Majesty’s Consul for the East Coast of Africa.

Zambezi Expedition

The British government agreed to fund Livingstone’s idea and he returned to Africa as head of the Zambezi Expedition to examine the natural resources of southeastern Africa and open up the River Zambezi. Unfortunately it turned out to be completely impassable to boats past the Cabora Bassa rapids, a series of cataracts and rapids that Livingstone had failed to explore on his earlier travels.

The River Nile

This house in Mikindani in southern Tanzania was the starting point for Livingstone's last expedition. He stayed here from 24 March to 7 April 1866

In January 1866, Livingstone returned to Africa, this time to Zanzibar, from where he set out to seek the source of the Nile. Setting out from the mouth of the Ruvuma river Livingstone’s assistants began deserting him. The Comoros Islanders had returned to Zanzibar and informed authorities that Livingstone had died.

Lake Malawi

He reached Lake Malawi on 6 August, by which time most of his supplies, including all his medicines, had been stolen. Livingstone then travelled through swamps in the direction of Lake Tanganyika.

With his health declining he sent a message to Zanzibar requesting supplies be sent to Ujiji and he then headed west. Forced by ill health to travel with slave traders he arrived at Lake Mweru on 8 November 1867 and continued on, travelling south to become the first European to see Lake Bangweulu. Finding the Lualaba River, Livingstone decided it was the “real” Nile, but in fact it flows to the Upper Congo Lake. In March 1869 Livingstone, suffering from pneumonia, arrived in Ujiji to find his supplies stolen. Coming down with cholera and tropical ulcers on his feet he was again forced to rely on slave traders to get him as far as Bambara where he was caught by the wet season. With no supplies, Livingstone had to eat his meals in a roped off open enclosure for the entertainment of the natives in return for food. Following the end of the wet season he returned to Ujiji arriving on 23 October 1871.

Lake Tanganyika

Although Livingstone was wrong about the Nile, he discovered for Western science numerous geographical features, such as Lake Ngami, Lake Malawi, and Lake Bangweulu in addition to Victoria Falls mentioned above. He filled in details of Lake Tanganyika, Lake Mweru and the course of many rivers, especially the upper Zambezi, and his observations enabled large regions to be mapped which previously had been blank.

Even so, the furthest north he reached, the north end of Lake Tanganyika, was still south of the Equator and he did not penetrate the rainforest of the River Congo any further downstream than Ntangwe near Misisi.

Livingstone was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society of London and was made a Fellow of the society, with which he had a strong association for the rest of his life.

Stanley Meeting

Livingstone completely lost contact with the outside world for six years and was ill for most of the last four years of his life.

Henry Morton Stanley, who had been sent to find him by the New York Herald newspaper in 1869, found Livingstone in the town of Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika on 27 October 1871.

Despite Stanley’s urgings, Livingstone was determined not to leave Africa until his mission was complete. His illness made him confused and he had judgment difficulties at the end of his life.

He explored the Lualaba and, failing to find connections to the Nile, returned to Lake Bangweulu and its swamps to explore possible rivers flowing out northwards.

His Final Breath

David Livingstone died in that area in Chief Chitambo’s village at Ilala southeast of Lake Bangweulu in North-Western Rhodesia, on 1 May 1873 from malaria and internal bleeding caused by dysentery.

He took his final breaths while kneeling in prayer at his bedside. (His journal indicates that the date of his death would have been 1 May, but his attendants noted the date as 4 May, which they carved on a tree and later reported; this is the date on his grave.)

Livingstone’s Body

Britain wanted the body to give it a proper ceremony, but the tribe would not give his body to them. Finally they relented, but cut the heart out and put a note on the body that said, “You can have his body, but his heart belongs in Africa!” Livingstone’s heart was buried under a Mvula tree near the spot where he died, now the site of the Livingstone Memorial. His body together with his journal was carried over a thousand miles by his loyal attendants Chuma and Susi, and was returned to Britain for burial. After lying in repose at No.1 Savile Row—then the headquarters of the Royal Geographic Society, now the home of bespoke tailors Gieves & Hawkes— his remaining remains were interred at Westminster Abbey.

Tested to the Limits

David Livingstone had to walk across an Africa that had no roads, no bridges, no shops and no hospitals. Neither was clean water available. He was a pioneer in the true sense of the word. After his first missionary journey Livingstone reported:

“I’ve drunk water swarming with insects, thick with mud, putrid with rhinoceros urine and buffalo dung.’”

Walking for days in pouring rain, hacking his way through dense rain forests, totally drenched by the equatorial rains, with his equipment either rotting or rusting, Livingstone persevered across the continent of Africa. Hostile tribes demanded exorbitant payment for crossing their territory. He was frequently in danger from Muslim slave raiders and like the apostle Paul was ” in perils in the wilderness”. He was charged by rhino, mauled by a lion, and debilitated with fever on over 60 occasions. The afflictions Livingstone tested him to the limits of human endurance while pioneering the mission field of Africa and opposing the slave trade. Putsi flies, leeches, maggots, huge sores, cholera, pneumonia, sunburn, tropical ulcers and malaria plagued him.

His Indomitable Spirit

Yet, his indomitable spirit rose above all challenges as he set his heart to accomplish for Christ that which seemed humanly impossible. He persevered and as a result of his sacrificial labours the slave trade in Eastern and Central Africa was exposed and eradicated.

Many hundreds of men and women who devoted their lives to African missions were inspired by David Livingstone’s steadfast example to be used by the Lord to reach the lost. For example, Dr. Kenneth Fraser was inspired to go to Moruland in Southern Sudan and Mary Slessor went to Calabar (present day Nigeria).

Acknowledgements: References: